Kitsap County gets almost all of the water we rely on from rainfall. This seeps into the ground and into aquifers where it is then drawn out via wells. The proposed high density development would be located on a critical aquifer recharge area, putting our local drinking water resources at risk.

Critical aquifer recharge areas must be protected. Once an aquifer is contaminated, there is no easy restoration process.

The proposed development would also threaten the many creeks and streams that flow into Gamble Bay. Keeping these waters safe is essential to preserving the region's shellfish and fish, which are essential for the local tribes like the Port Gamble S'Klallam and Suquamish.

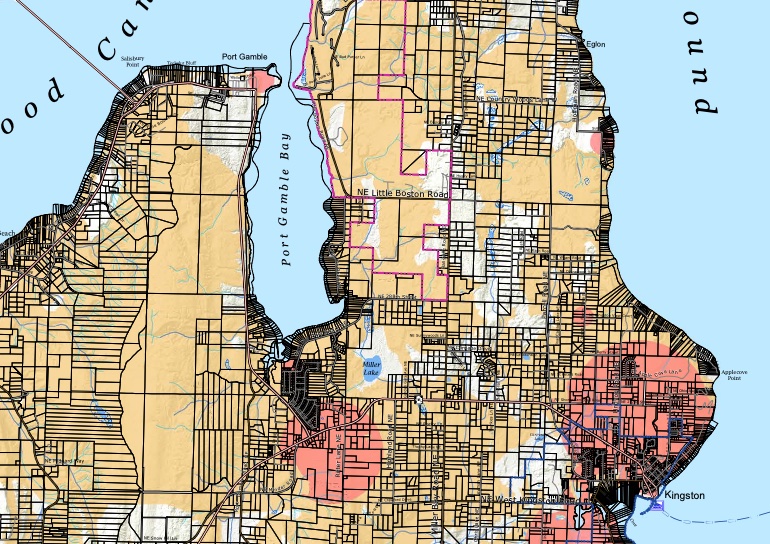

Learn more about North Kitsap's streams, aquifers, and current zoning on our maps page.

Planning the future of water in Kitsap by Melissa Fleming

Water resources require more management in Kitsap than most Washington counties because our water comes entirely from groundwater renewed by rainfall rather than from rivers renewed by snow melt. Groundwater and numerous wetlands are also responsible for maintaining stream flows, which provide fish and wildlife habitat and support hatcheries and irrigation. Concerns about maintaining the quality and quantity of water drive many county regulations around development in Kitsap County.

In 2023-2024, Kitsap County is conducting a periodic update of our 20-year comprehensive plan and critical areas ordinance (CAO), as called for in the state’s Growth Management Act. The comp plan is a multifaceted vision of how growth should proceed in unincorporated Kitsap County over the next 10-20 years. The CAO is a set of regulations county planners use to protect the environment and public safety when evaluating proposed development. The five interdependent critical area types are Wetlands, Critical Aquifer Recharge, Frequently Flooded, Fish and Wildlife Habitat Conservation, and Geologically Hazardous areas. This article is a brief introduction to some of the issues being discussed concerning wetlands and aquifers.

Wetlands provide essential habitat for young salmonids and amphibians, help control flooding during heavy rains, and contribute to stream flows and recharge groundwater in summer. Buffer zones are required to avoid or minimize the impact of development on these wetland functions. CAO revisions include better specifying required conditions of buffer zones, e.g., that buffers should be vegetated with native species. Circumstances in which buffer width reductions are allowed are also being clarified, as are exemptions for small wetlands.

Recharge of our numerous aquifers naturally occurs wherever rainfall reaches the ground, except on impermeable surfaces like pavement or bedrock outcrops. Soil filters out many potential contaminants as surface water and precipitation infiltrate through to aquifers beneath. Critical aquifer recharge areas (CARA) are designated around existing wells and known places where soil and geology could allow contaminants to reach aquifers used for drinking water. Thus, CARA regulations focus on businesses involving biological or chemical hazards with the potential to adversely affect drinking water supplies quickly and substantially, but not on most residential or other land uses where potential pollution can be mitigated with appropriate septic and stormwater systems, including raingardens and bioswales.

Quantities of groundwater available vary greatly across the county and throughout the year. Areas in southwestern Kitsap receive 2-3 times the precipitation of areas furthest north. Ten times more rain falls in early winter than in late summer. For decades, KPUD has been building infrastructure to transport water from wetter to drier parts of the county to accommodate population growth. In summer, water drawn for human use has reduced groundwater needed to maintain stream and lake levels, leading to moratoria on new wells in some communities. Too much groundwater withdrawn near the shoreline can lead to saltwater intrusion into wells. Critical areas maps are incomplete because mapping efforts are expensive. Thus, how proposed development might affect water resources is often not fully understood until permits are applied for and wetlands and hydrological reports, paid for by the permitees, are submitted.

While the CAO provides tools for avoiding, minimizing, or mitigating proposed land use, the comprehensive plan sets broader goals for meeting the basic needs of a growing populace while maintaining elements important to residents, like “rural character”. Two very different alternatives were proposed to provide scope for the EIS. “Focused Growth” would direct more development to existing Urban Growth Areas (UGAs), leaving more rural lands for agriculture, natural resources, and fish and wildlife habitat. “Dispersed growth” would approve more requests for rural zone reclassifications (also summarized on the Comp Plan Update website), mostly to higher single-family housing densities more profitable for developers. The final plan can include parts of both alternatives and the CAO applies equally within UGAs and outside them.

Maintaining status quo is not an alternative because population growth is inevitable - but these updates are an excellent opportunity for public input into what that growth should look like. Limiting the upzoning of a rural parcel to higher density single family housing during this update does not necessarily forestall more intensive development of that same land at a future date. On the other hand, allowing denser development on rural parcels now does preclude a diversity of other potential land uses, including small-scale agriculture and value-added forestry, recreation, tourism, and natural environments.

Drafts of the Comp Plan update, Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and other associated documents are now available on the county’s website and public comments are welcome. The Draft CAO should be available in March. The Puget Sound Regional Council has extensive resources to help county’s evaluate whether their comprehensive plans and CAOs align with Puget Sound recovery goals

This checklist is an excellent guide to form questions and comments during Kitsap County Comprehensive Plan comment period.

(Puget Sound National Estuary Sound Choices Check list 2023).

Paper by Stephen Howard

While the concept of the sports facility is good, the site has some problems, most of which involve water. I could talk about the potential for noise and light contamination of the Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park, the possibility of an endangered species residing in or near the planned site, the heat-islands created by the asphalt and structures. I could mention the potential for increased traffic in the area of SR104/SR307 to increase the number of traffic accidents, or the near-dearth of bus traffic to that area, but those aren’t water, so I’ll get to that subject.

First, the proposed facility would lie in an area designated as “Category II critical aquifer recharge area” by Kitsap County. That is defined as “Provide recharge to aquifers that are current or will become potable water supplies and are vulnerable to contamination based on the type of land use activity” per https://spf.kitsapgov.com/dcd/DCD%20GIS%20Maps/Critical_Aquifer_Recharge_Areas.pdf

I am sure that some are asking themselves “How Could a sports facility contaminate the aquifer”, so I will explain. The facility will have to have access-roads, parking, side-walks, and paved courts. Those are impermeable surfaces, and runoff water from such are considered contaminated, because of the chemicals in the asphalt, and substances deposited by vehicular traffic, onto the asphalt. That water would have to be managed so as to prevent aquifer contamination, and contamination of the streams shown on the map of the proposed site, and of the Port Gamble inlet, on which a major and lengthy cleanup was recently completed to remove contaminants from the old mill-site.

So, how much contaminated runoff are we talking about? The area in question is, per Kitsap County measurements, listed as receiving 30-40 inches of rain per year.

That equals 24.93 gallons per square foot. That doesn’t sound like much at first. The average parking-space is 8' by 16', for 128 SqFt, so each parking spot sheds up to 3,191 gallons per year. There will be much more paved area than 128 square feet. That is both a lot of water not getting into the aquifer, and a lot of contaminated water to be dealt with. What are the contaminants we’re talking about? For starters, petrochemicals from the asphalt itself. Add to that every fluid that a motor vehicle uses, Oil, brake fluid, transmission fluid, coolant. And then there’s one most folks aren’t aware of, the antioxidants that make up part of the rubber in their tires. The chemical, 6PPD, is lethal to Salmon at LC50 levels of 0.095 μg/L.

Washington, Oregon, Vermont, Rhode Island and Connecticut, in addition to several tribes, including the Port Gamble S’klallam tribe, have written the EPA, citing the chemical's "unreasonable threat" to their waters and fisheries. And, that same chemical is used in the artificial turf sports fields, in the form of ground rubber, from recycled tires, so, if artificial turf is used, all the rainwater that falls on those becomes toxic waste which must be prevented from entering the aquifer or from running off into the sound. Preventing it from entering the ground is not possible with standard artificial turf construction. There are two creeks shown on the crude map provided by Raydient that run towards Gamble inlet, which would rapidly transfer the chemical into those waters.

How does one deal with Storm-drainage? Storm drainage culverts, or the sewage system. There are none of either anywhere near the site, yet the drainage must be collected and processed. Running either of these options to the site would be very expensive, as all trenching and pipe-laying operations are, especially when they follow the easement for state highways, due to state D.O.T. involvement. Storm-water collection systems are never 100% effective, so contamination of the aquifer is inevitable if this proposal goes forward.

In addition to that, as anyone who has been past the proposed site has seen, it is NOT level. Major excavations and soil disruptions would be needed to get the level area required for the fields proposed. Those excavations will disrupt the aquifer, reducing the percolation of rainwater into the aquifer.

Now to deal with water TO the site. Water will be needed for drinking, sanitation, grounds-maintenance, and fire-flow. Per KPUD, extending water main costs, at best, per conversations with Mike Flaherty of KPUD, at least $100 per foot, and increases greatly with elevation-changes, wetlands crossings, and especially with state highway rights-of-way, that, again, due to requisite state DOT involvement. The option, instead of extending mains, is a well. That will have to be a rather substantial well, just to handle peak event-use. That leaves fire-flow. Wells do not normally suffice for fire-flow because of the sheer volume of water required, not to mention that fighting a fire can result in power to the site being cut, eliminating the pumps. Without fire-flow, you cannot get insurance for occupiable buildings, nor, indeed, occupancy permits.

Another issue is, with reduction of input to the aquifer due to development and disruption, and the increasing draw on the aquifer, you increase the likelihood of saltwater intrusion. We’re surrounded by salt water, and the only thing keeping it from infiltrating is the outflow through the soil and rock of fresh water. Desalination is difficult, slow, inefficient, and expensive, and none of the public utility districts have the means to start doing this. The only response available would be to stop drawing water from the affected wells, and shift the load to other wells. This sets up a domino-effect, because then those areas loose more fresh water, and becomes subject to saltwater intrusion. The more wells you shut down, the greater the drain on the remaining, and it just continues.

Now we need to get back to water from the site. Sewage-water to be precise. As previously mentioned, sewage-mains aren’t on or near the site. That leaves either the expensive connection option, or a septic system. Any such system would have to be much larger than a home-sized system to handle major event use. The permissibility of such on the proposed site at the scale needed would require determination by the county, and, given the potential for drain-field contamination of the aquifer, may not be granted. The idea of a major septic system in a Critical aquifer Recharge Area leaves a foul taste at the back of my mouth

What is the option that eliminates these problems? Obtaining a parcel that already has, or could economically acquire, the requisite water supply, including fire-flow, that has sewage, and storm drainage adjacent-to or within easy reach, and that doesn’t occupy or lie adjacent to a critical aquifer recharge area or have streams that flow to the sound running across it. That it would be within easier reach of the community would also be a benefit.

Why was this site suggested? It is my supposition that the whole proposal is intended as “Incentive” for the folks in Port Orchard to grant a re-zone that would allow development of home tracts on the site. Raydient has stated, at their first two meetings on this issue, that they are no longer going to be logging the site. The current zoning prevents home building or any other development. This limits or eliminates any sales of that land, and as long as Rayonier owns it, they have to pay the taxes on it. It was also stated at the previous meetings that Raydient’s foreign investors, which we were told comprise over 50% of the investors, weren’t keen on just donating all the land to the county. These foreign investors would not feel any impact to our aquifer. By donating a developed site, which it is being hinted and alluded-to that they may after site development is complete, they get a larger tax write-off than for an undeveloped site. I also hold that the fronting of this as being solely “For the children” is bogus, given that, at the very first public meeting, the subject of including a sports bar and restaurant on the site was put forth. Child-athletes don’t use sports bars, and their parents are only going to be field-side cheering-on their athlete. This is all as part of raising the property-values. The proposed re-zoning for this site would also establish precedent for the incremental re-zoning of the entirety of their lands. That the re-zoning would allow homes brings a further contamination potential for the aquifer. Fertilizers and herbicides don’t belong in drinking water. The expenses of developing a problematic-at-best site, born by the citizenry, would be more beneficial to the current owners than to the citizenry that may use the site. If the monies saved from the expensive infrastructure access that would be required, and environmental contamination control efforts and facilities needed, IF permits could even be granted, were instead put towards a more feasible and less-destructive facility could be brought into being far quicker and easier.